Emergency-response platform is put to the test in NATO exercise

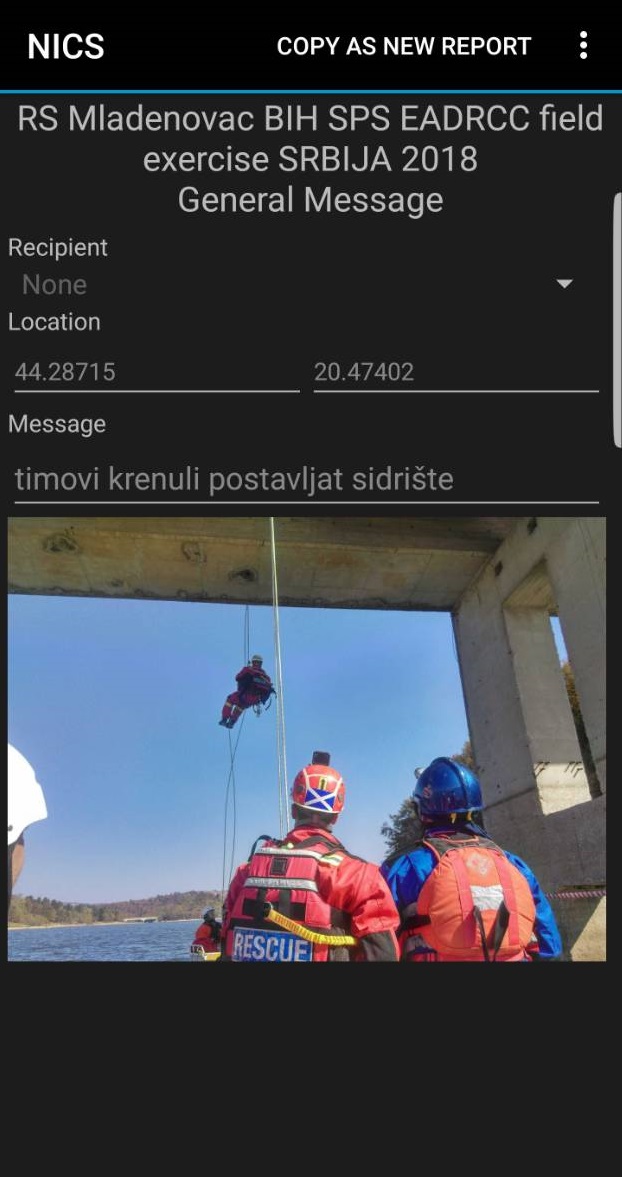

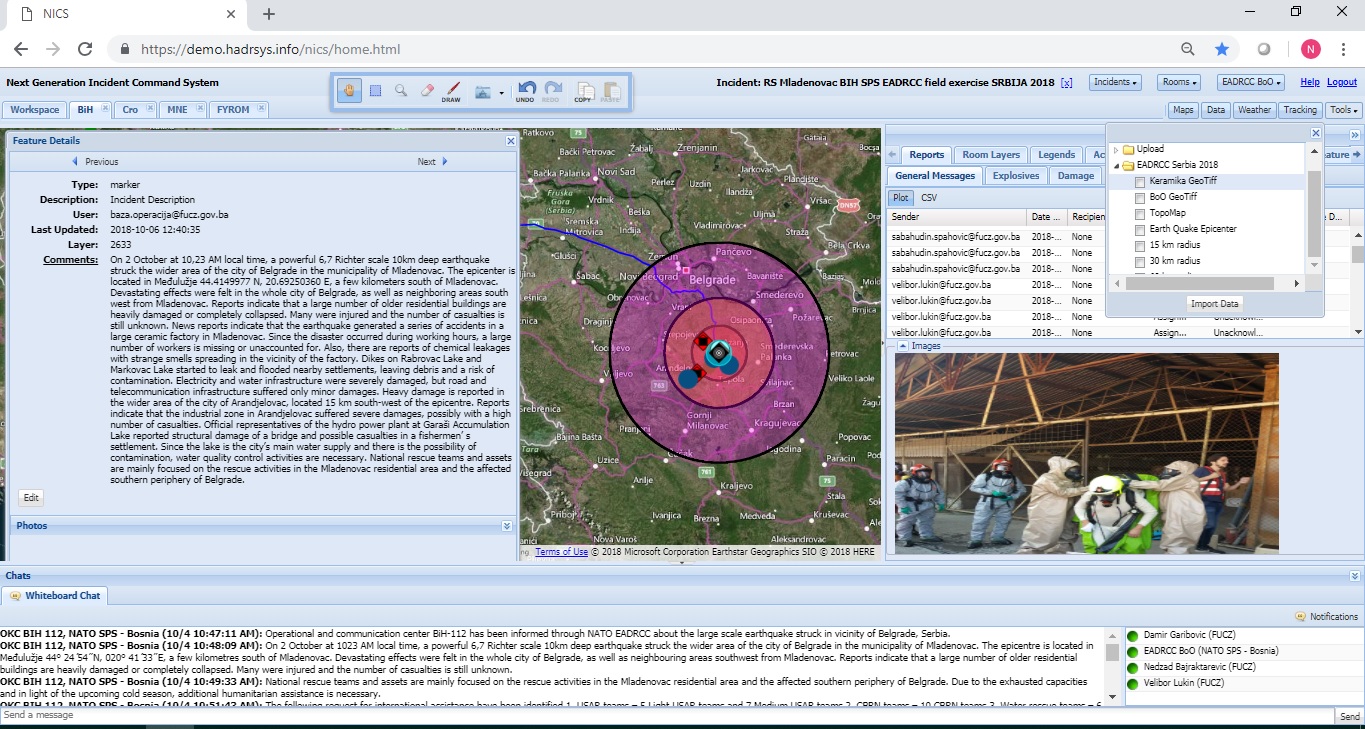

The first water rescue on Garaš Lake in Serbia had just begun. Emergency personnel still on their way to the scene and the commander back at base station watched it unfold: a photo of a responder being lowered from a bridge above the lake had been uploaded to the Next-Generation Incident Command System (NICS).

The communications platform, which the personnel were monitoring from their cell phones, was being used to coordinate rescue actions after a disastrous earthquake — a mock earthquake scenario, that is, set during the NATO Euro-Atlantic Disaster Response Coordination Centre Consequence Management Exercise.

Two thousand personnel from 40 countries participated in the exercise held from October 8 to 11. Among them were emergency responders from Bosnia and Herzegovina (BiH), Croatia, Montenegro, and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia who used the exercise as an opportunity to test NICS.

NICS was developed by Lincoln Laboratory and the Department of Homeland Security Science and Technology Directorate nearly a decade ago. The web-based communications platform, which emergency personnel access by logging into the NICS application on their cell phone or computer, allows them to quickly share information about an emergency incident and collaborate on response actions. Dozens of emergency response agencies around the world use NICS today.

Two years ago, the NATO Science for Peace and Security Programme asked the Laboratory to adapt the platform for users in BiH, Croatia, Montenegro, and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Since then, Laboratory staff have worked closely with emergency agencies in each of the countries to adapt NICS to their disaster-response needs and in ways that could improve communication across country borders. The vision is for NICS to allow these neighboring countries to work together seamlessly if a disaster were to strike the region.

"There were massive upgrades to NICS this year," said Stephanie Foster, the project manager at Lincoln Laboratory. Foster traveled to Serbia for the exercise with Christopher Budny and Jared Pullen, both of the Humanitarian Assistance and Disaster Relief Systems Group. To prepare for the exercise, the Laboratory team created a new workspace in NICS where the exercise could be implemented, and worked with the countries to prepopulate geospatial information into the system. From there, emergency agencies from each country ran with the system.

"They are adapting NICS to improve their crisis management capabilities nationally. They're really embracing it," said Foster.

During the exercise, responders reacted to three earthquake-fallout scenarios: urban search and rescue missions among rubble, water rescues necessitated by dam breakages, and chemical spills in the area around the town of Mladenovac, Serbia. When a simulated emergency call came in, a commander at a base camp sent responders to the scene and created an "incident" in NICS.

At the core of NICS is the incident map, which displays real-time information, such as incident perimeters, evacuation zones, weather conditions, and images from the scene. Theses visual tools are especially helpful for working across language barriers. The information displayed on the map is inputted automatically by data sources (for example, the GPS locations of responders) or manually by the emergency personnel.

"Unlike other geographic information systems, NICS makes it possible for a large number of users to work in the system and to deliver and gather information within their jurisdiction in real time," Mirnesa Softić stated in a post-exercise report. Softić is the NICS project co-director from the Ministry of Security in BiH and joined Foster in briefing the NATO Secretary General Jens Stoltenberg on NICS during his visit to the exercise. They were joined at the exercise by fellow NICS project co-directors Nikola Krizmanic of Croatia, Urim Vejseli of the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia, and Đorđije Vujović of Montenegro.

NICS was first tested with the partner countries last year during a similar NATO exercise. As they did after that exercise, the team is now analyzing the data to see what improvements can be made to the system in upcoming "development sprints," as Foster put it.

"Probably the biggest thing we are finding is the need to filter specific data in NICS that used to be 'incident wide,' like tracking locations of all mobile users or listing all photos from the scene," said Foster.

This recent test of the system was unique for NICS because three types of responses (urban, water, and chemical) occurred in the system at the same time. The system was originally developed exclusively for wildfire responses, so having incident-wide data was useful for that application. But now the developers are finding that, with different and simultaneous responses, too much unrelated data can muddy the waters.

"We are seeing that the urban search-and-rescue team should be tracked separately from water rescue. We still want all of the data available to everyone in the incident; maybe water rescue wants to see where urban search-and-rescue is. But they shouldn't have to work to filter through data to find what they need," Foster said.

The team plans on doing another full year of updates to NICS for the NATO project. According to Softić, teams within four national institutions of BiH have already started using the system. By 2020, NICS should be fully transitioned to all four of the countries for operational use.